founding editor: bob caterrall

editor: city editors

editorial: The porous urban, -yimin zhao

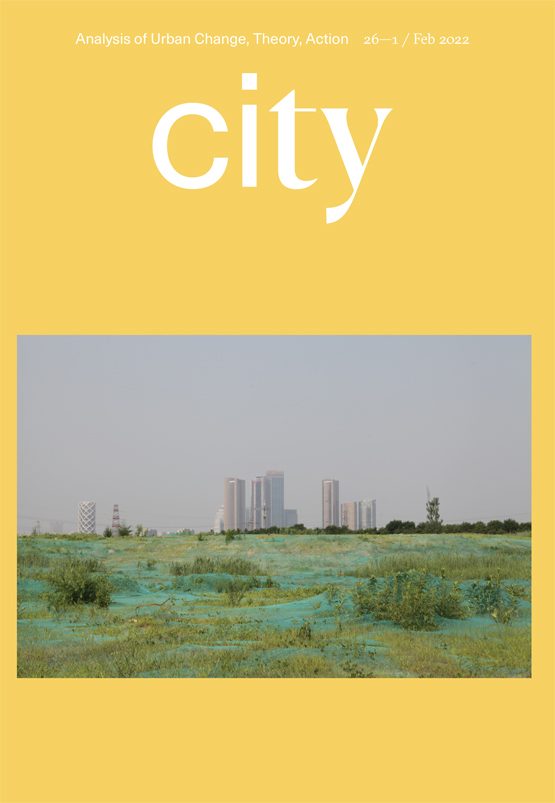

I have just finished a spell of fieldwork in Shunde, an (extra-)ordinary city in Pearl River Delta. A place struggling with its not-yet-urban-enough landscapes, this city hosts many influential enterprises (and even industries) in the global production chain of household appliances and hence becomes a key part of the ‘World’s Factory.’ What attracts me to visit here, though, is not its crucial role in the global production chain, but instead for the fact that it also nurtures one of the world’s largest property developers. More interestingly, this developer was only a local town and village enterprise (TVE) thirty years ago. Investing heavily in robotics, it is now placing itself at the frontier of the trend of automation in the construction industry. Yet, when I arrived at this field site, I was at once shocked by the topography of this developer’s headquarters (see Figure 1).

While many high-rise buildings have been erected, this area is by and large rural from the local residents’ point of view. Those buildings are surrounded by villages and agricultural land, mostly for nursery gardens and orchards to cultivate ornamental plants (such as the New Year Oranges in Figure 1). Located at the boundary between two big cities in the Great Bay Area, plenty of property projects have been developed here, ranging from villas to multi-storey and high-rise residential units. Nevertheless, there is always an invisible wall separating those ‘urban’ communities from their rural surroundings. This could be labelled as a kind of ‘enclave urbanism’—in terms of segregated and gated developments with various boundaries that demarcate the urban, inducing new forms of exclusion (Douglass, Wissink, and Van Kempen 2012, 169). But I think this label per se might not be adequate to illustrate well the local ecology of urbanisation. Many residents in these enclaves, for instance, might appeal to the surrounding ‘rural’ communities in terms of their children’s education or even of their own businesses. On the other hand, this developer is also inspired by the co-existence of the urban way of life and its surrounding ‘natural’ (not-yet-urban) landscapes, and starts to wrap up a new model of property development through their own conception of ‘green urbanism’ (Koh, Zhao, and Shin 2021).

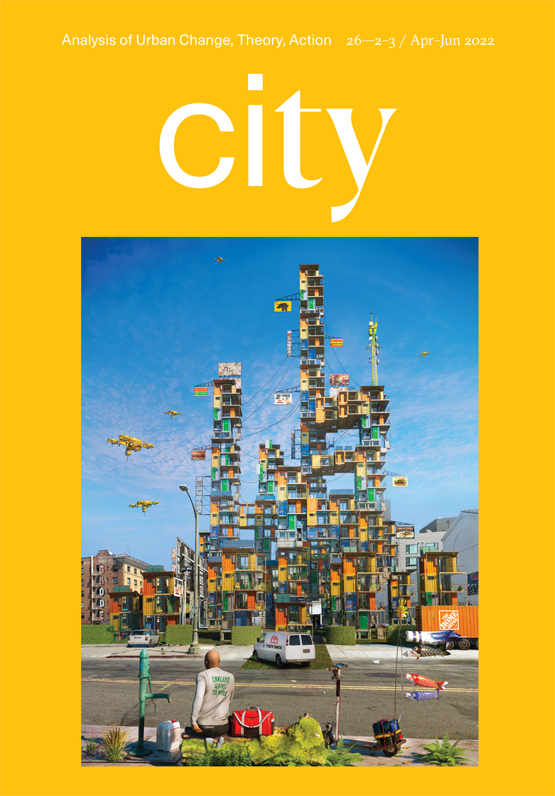

Instead of highlighting the separation and segregation between the urban and the rural, or between the enclave and its outside, I think it might be better to look into this phenomenon through the lens of porosity. In a visit paid to Naples in 1924, Walter Benjamin was also shocked when seeing that ‘the stamp of the definitive is avoided,’ and that ‘no figure asserts its “thus and not otherwise”’ (Benjamin 1979, 169). In this sense, he deploys the concept porosity to elaborate the situation where spatial boundaries and divisions are absent and the passion for improvisation accommodated (Benjamin 1979, 170; see also Gilloch 1996, 25–26). In the urban transformation of the global South, porous scenes like the one in Shunde are not exceptional or unique. We are indeed living through the urban processes and have no clear clue of what they might look like since the ‘stamp’ of a definitive urban has to be developed and conceptualised, which is always subject to contestations. The world’s largest developer might locate its headquarters in a ‘rural’ area, surrounded by New Year Oranges. Meanwhile, villages might also thrive within the urban landscapes, as evinced by numerous ‘urban villages’ in the Pearl River Delta (see Figure 2) and India. There might or might not be a planetary logic/mechanism underlying such scenes, but we do observe porosity in all such cases to certain extents.

to read this editorial in full, please click here.