founding editor: bob caterrall

editor: city editors

editorial: Urban phantasmagorias, -brandi summers

I don’t predict the future. All I do is look around at the problems we are neglecting now and give them about 30 years to grow into full-fledged disasters. (Octavia Butler, 2000)

We have officially entered our third year of the global pandemic with no indication that transmission of the deadly virus will wane anytime soon. As of January 2022, the global death toll surpassed 5.5 million, however as some data scientists have argued, this figure is grossly underestimated without accounting for excess mortality—‘a metric that involves comparing all deaths recorded with those expected to occur’ (Adam 2022, 312). Prevailing data that show that COVID continues to disproportionately kill poor, racialized minorities worldwide—highlighting stark inequities of health along class, racial and ethnic lines. The impact of the pandemic has extended beyond concerns about health since we have seen a spate of developments occur that disproportionately affect marginalized populations all over the globe. We are witnessing an expansion of segregation, poverty, unemployment, and homelessness via evictions, while racial and class-based disparities in education access continue to plague the world’s most vulnerable people. The impact of this global crisis has shifted our sense of the world, and our relationship to public and private spaces. We are seeing the effects of the privatization of social reproduction, and uneven patterns of (im)mobility, especially as the exploitation and devaluation of racialized and feminized care labor has been intensified. In other words, the global pandemic has exposed what gets invisiblized via processes and practices associated with racial capitalism, gentrification and neoliberal urbanism. Now in 2022, we are still in the throes of what David Madden (2020) described in a previous City editorial as ‘Covid capitalism’—one that is exhibited through crisis, austerity, risk and authoritarianism. In so many ways, the pandemic is shining a light on social fabrics and urban processes that were being eroded by gentrification, making room for platform mediated exchanges. The ‘smart’ and ‘resilient’ cities are not necessarily ‘just.’ In other words, the pandemic has effectively accelerated disruptive processes already in progress.

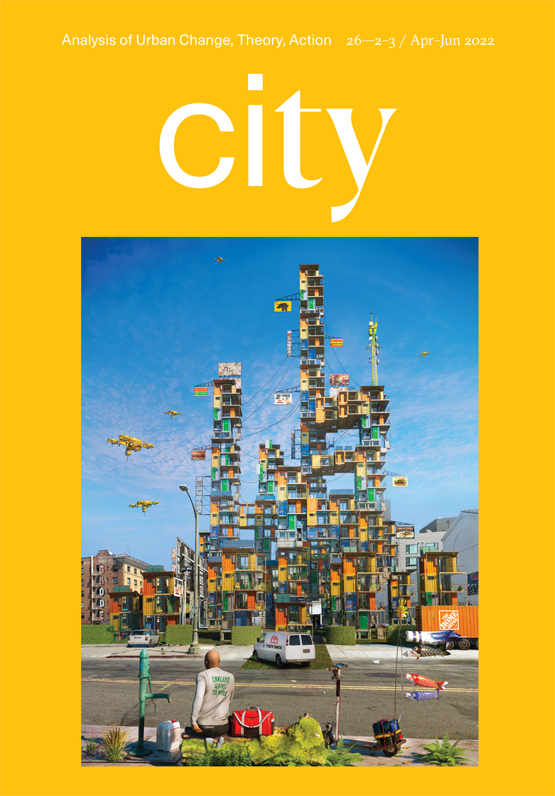

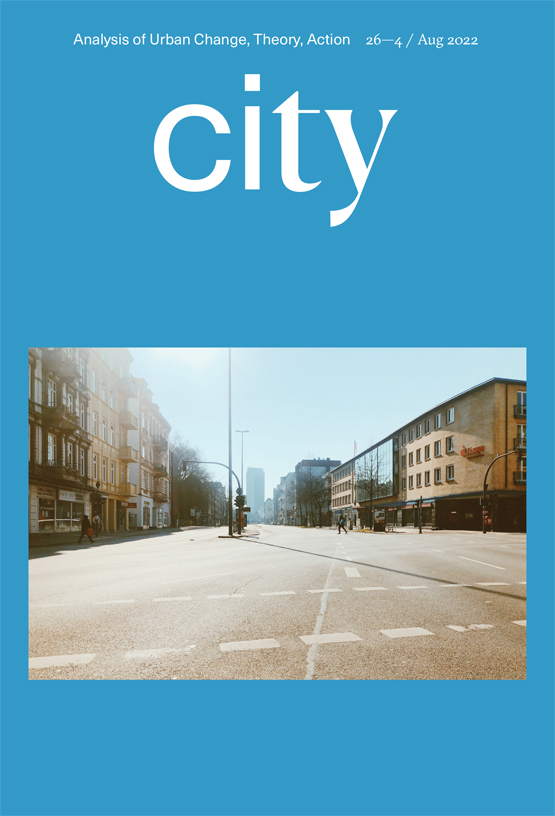

I live in the United States, and when the city of Berkeley (California) enforced the first lockdown of the pandemic in March 2020, I decided to revisit some of my most favorite and captivating science fiction novels. I poured over fantastic(al) stories by Octavia Butler, China Mièville, N. K. Jemison, and Nnedi Okorafor. I decided to read Max Brooks’ World War Z because I wanted to better understand what was happening, but most importantly, what future we were poised to enter. Like in World War Z, it became clear that the pandemic had exposed faulty infrastructure and bad policy. Most notably, the pandemic exacerbated miscommunication between nations, xenophobia, greed, poverty, destitution, and the survival of capitalism through it all. Naturally, this deep dive into the dystopian worlds delicately constructed by some of our most creative literary thinkers got me thinking about how to digest the spectral images I saw on social media—empty amusement parks (in Los Angeles), desolate central business districts (in London), bountiful waterways reclaimed by wildlife (in Venice), residential apartment buildings engulfed by flames (in New York) (see Figure 1).

To my mind, our haunted reality has become completely aligned with, and perhaps more jarring than fiction. Stories about ‘ghost kitchens’ and ‘dark stores’ solidify city life as part of ‘urban capitalist simulacra’ (Summers 2019, 3), a Baudrillardian simulated ‘reality,’ conscripted by technological hegemony. Dark stores are fulfillment centers used by delivery apps as storage facilities that are not open to the public, but most often take up commercial space. Ghost kitchens are virtual restaurants, or meal-preparation facilities that are untethered from physical restaurants. These spaces, often located in commercial districts, require significantly less labor and curb overhead costs associated with running a brick-and-mortar establishment. Dark stores and ghost kitchens existed before the pandemic, but are taking on new forms given the accelerated demand for deliveries (thus expanding the market for third-party online delivery providers like DoorDash, UberEats, and GrubHub). Both also contribute to a city that has been overrun by laborers in motion, navigating the city as they deliver goods to people who can afford to order from the technology companies that barely pay the laborers’ minimum wage. At the same time, these shadowy spaces presume human, or consumer absence.

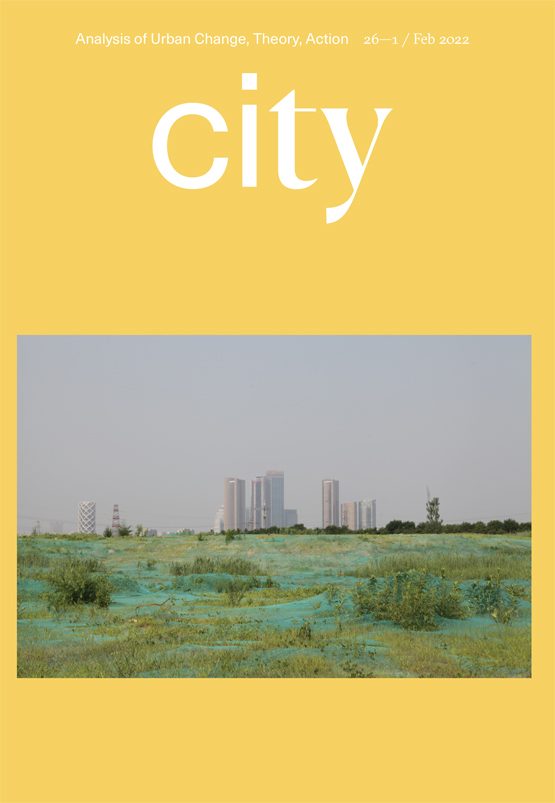

Our entrance into the post-industrial economic landscape has been punctuated by a political economy of ghoulish geographic absence and liminality. Urbanists have previously characterized neoliberalism, and by extension, neoliberal urbanism, as undead (Peck 2010; Peck, Theodore, and Brenner 2013; Aalbers 2013). In fact, Manuel Aalbers (2013) identifies neoliberalism as a ‘zombie’ (2013, 1089), making room for us to consider a kind of ‘zombie capitalism’ that is not alive, ‘but somehow fantastically continues and threatens to destroy the existing economic order’ (Tabb 2014, 97). It is in cities that both growth and decay exist in the same spaces at the same time. The proliferation and exacerbation of platform urbanism makes sense in the COVID era, with the pandemic mapping easily onto the social order of financial capitalism. This is inherently tied to uses of space. As Matthew Soules (2021) writes, one of the byproducts of financial capitalism’s focus on asset value over use value is the underuse of architectural space (zombie urbanism) and unoccupied real estate (ghost urbanism). Phantasmal forms of contemporary urbanism have flipped the organizing terms and images of blight, decay, and ruin to signal vitality and economic growth. Historically, urban spaces designated as blighted and uninhabitable have been some of the prime areas where poor, immigrant, and racially marginalized people have and continue to live. Zombie urbanism is trenchant under-occupancy in areas that ‘mix present populations with [presumably] absent populations, exhibiting eerily low levels of vitality in relation to their scale’ (Soules 2021, 51). Ghost urbanism, on the other hand, is exhibited by the dramatic proportion of vacant, or unfinished units ‘in the context of a perceived crisis’ (Soules 2021, 51). Both modes of ethereal urbanism haunt cityscapes across the world; littering urban landscapes with architectural carcasses that concretize the material excesses of greed and plunder.

to read this editorial in full, please click here.