founding editor: bob caterrall

editor: city editors

editorial: Campaigning in the time of coronavirus

Last week, in the midst of lockdown, I attended a DPAC (Disabled People Against Cuts) online event for Ellen Clifford’s book launch and rally (DPAC 2020a). Ellen’s book, The War on Disabled People (2020), recounts DPAC’s struggles against the past decade of austerity in the UK, situated in the historical context of exclusionary capitalism, whilst providing a contemporary activists’ guide for a more socially-just alternative. Ellen said the hardest thing about writing her (brilliant) book was not the writing or the research, but the authorial demand that she put herself forward as an individual, not as a collective. The book launch, therefore, was a deliberate return to collaboration, consisting of a rapid and rousing succession of speakers, a solidarity event kick-started by a radical poem and accompanied by kick-ass live music. The event brought DPAC campaigners and supporters together, eliding space as participants connected from across the UK, Greece, the United States and Uganda. A solidarity event full of love, shared pain, remembrance and intention.

This is just one example of campaigning in the time of coronavirus. Writing about a moving target is an unstable business, but we can begin to think about what new connections, concepts, practices and potentials are emerging from the technologies of lockdown and the modalities of crisis. The calm and the storms of these Covid-19 times are generating new forms of struggle, a hybrid urbanism (Leontidou 2015, 2020) combining online and on-the-streets campaigning, generating a productive dialectic. I speak from my position in London, the UK, but try to make sense of what I have heard and observed through my own campaign networks of resistance in the broader international context.

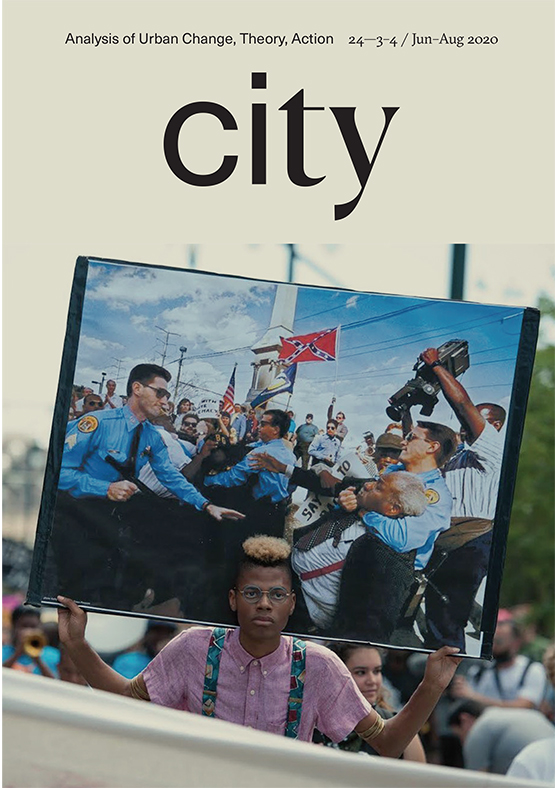

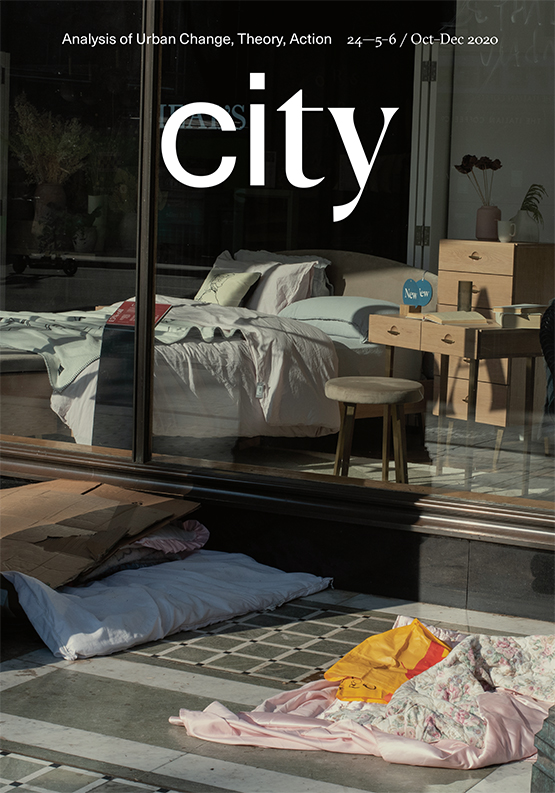

It may seem ironic that while we are being contained in so many spatial, social and economic ways during the coronavirus pandemic, resistance is being unleashed in force, en masse and in multiple ways. Campaigning during Covid-19 is as large as the thousands of movements marching under the banner of Black Lives Matter and as small as a local North London campaign up the road from where I live to prevent one young woman from being illegally evicted (not small for her of course, scale shifts depending where you stand). Yet, understood from the perspective of escalating need, this flourishing of struggle is not ironic but necessary, in order to address the emerging health and economic crises that are exacerbating the racialised, classed, gendered and disabling fault lines of inequality and injustice in such devastating ways, manifested through uneven distributions of job loss, debt, evictions, sickness and safety net. As the social injustices unfold, so too do the resistances against them. Not only the multiple protests mobilised under the banner of Black Lives Matter, but in so many localised ways, from the occupation of the Capital Hill Autonomous Zone in Seattle, to a health workers’ protest in Cape Town outside Tygerberg Hospital demanding adequate protection equipment, to a socially-distanced human chain encircling an empty housing estate in East London (Kayz 2020; Focus E15, personal email June 15, 2020).

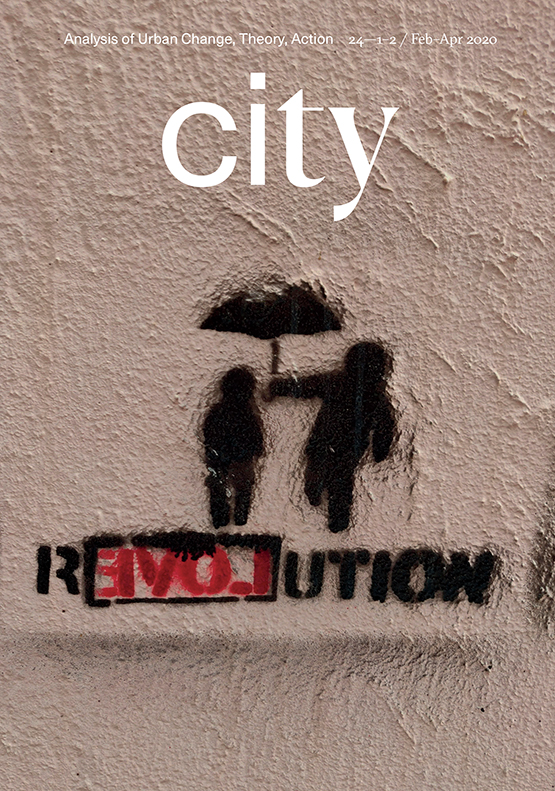

It is pertinent to call on the question of what geographies are involved in resistance, posed most recently in City by Ritterbusch and El Cilencio (2020) with reference to global South struggles in Colombia and Uganda. We can ask what new spaces and spatialities, bodies and embodiments, are involved in these yet continuing struggles against state violence and capitalist imperatives during the Covid-19 pandemic? If, as Ritterbusch and El Cilencio argue, revolution is situated in the streets, what does this mean for those locked down and locked in during the coronavirus crisis? As Simone Aspis, a disabled activist, pointed out, over 1.5 million disabled people in the UK who are currently “shielding” themselves are effectively under lock and key indefinitely (DPAC 2020a). Many are classed as “clinically extremely vulnerable” and urged to only leave home with extreme caution and strict social distancing (Public Health England 2020). What does this mean for DPAC whose direct actions focused on occupying city streets and asserting their demands in embodied collective ways (Humphry et al. 2020)?

A shift from embodied to virtual campaigning produces mixed benefits and barriers. Some campaigners miss the socialities and serendipitous connections of face-to-face meetings. Paula Peters, a disabled activist, says she misses organising around a table with a drink and shared food, “I miss the street protests and blocking the roads. I’m having withdrawal symptoms. But I don’t feel safe to go out on protests while the pandemic is happening” (personal email, June 20, 2020). However, some disabled people, who are routinely housebound, feel less marginalised as their locked-down experiences become mainstream and they have the chance to communicate via virtual meetings (Clifford 2020). But there are limits to the “grassroots smart city” (Leontidou 2020) as other disabled people find online platforms challenging to navigate or are excluded because they do not have access to the internet (Clifford 2020). Disparities in internet access can also exclude other groups, such as those on low-incomes or elderly people, while the global South/North digital divide, albeit with exceptions and nuances, still persists (Pollitzer 2019; DPAC 2020b).

However, for some, like myself, online campaigning has made it easier to pick up with struggles, old and new. Instead of having to navigate to a venue and negotiate face-to-face sociality, I just click online and I’m there. I can be invisible if I want and write my comments in the “chat” more confidently than I feel able to speak up in an embodied room full of people. Best of all, I can access with ease the astounding knowledge and energy from stalwart activists several nights a week. The importance of feeling part of a community for sustaining solidarities has long been recognised (Pulido 1996; Peña 2002) and for me the online communication enabled a gentler, less intimidating way to build a sense of belonging that felt so crucial at this time of lockdown. Charlotte Hughes (DPAC 2020b), a grassroots campaigner for The Poor Side of Life that exposes the unfair treatment of local benefit claimants, describes internet campaigning as “perfect” and “easy”. She says to others wanting to build local campaigns, “Online is amazing. It’s our world. So start at home on the internet talking to community groups and before you know you’ll get a lot of people talking to you. Get them to realise they don’t have to be outside to be involved. Online is perfect.” Homes for All is a UK national housing campaign, but being based in London skewed who attended meetings. However, now that organising meetings are held online, people from all over the UK join regularly, enabling broader solidarities. Public meetings reach even further. Previously they were a bi/annual event, usually all day to make good use of the time, labour and financial costs, but now they are monthly, shorter and free. This attracts more people, more often, and as the meetings are recorded, instead of hundreds of participants, there are thousands. Distant or busy speakers can more easily attend and the campaign has had tenant campaigners from Barcelona, the Bronx and Massachusetts, USA, sharing their organising strategies (Homes for All 2020). Similarly, Andy Greene of DPAC (2020a) welcomes the digital space as a platform for “bigger, wider conversations” that can build solidarities within and beyond DPAC. Moreover, the multiple recorded campaign meetings, panels and webinars being produced during Covid-19 are of great value in generating a large and accessible data resource.

to read this editorial in full, please click here.