founding editor: bob caterrall

editor: city editors

editorial: Polycritical city?

david madden

Housing crisis. Homelessness crisis. Climate crisis. Environmental crisis. Financial crisis. Debt crisis. Mortgage crisis. Supply chain crisis. Energy crisis. Cost of living crisis. Crisis of social reproduction. Crisis of care. Refugee crisis. Covid crisis. Opioid crisis. Health crisis. Water crisis. Air pollution crisis. Police violence crisis. Infrastructure crisis. Crisis of overaccumulation. Legitimation crisis. Urban crisis. The new urban crisis … .

This non-comprehensive list of crises describing contemporary urbanisation is not meant to diminish the seriousness of any of them, but to highlight their numerosity, depth, and pervasiveness. If 20th century urban studies, according to Taylor and Lang (2004, 951), ‘was relatively straightforward’ and characterised by an ever-present need to continuously theorise the urban condition through the production of new concepts such as ‘anti-city,’ ‘boomburb,’ ‘edge city’ or ‘exopolis,’ then 21st century urbanisation has made it necessary to refocus urban studies around the constant generation of new perspectives on urbanisation’s moments of crisis.

In a basic sense, the idea of crisis denotes a long-term problem, as opposed to an immediately resolvable conflict. But beyond that, the meaning of crisis as a diagnosis depends upon the theoretical framework and political project within which the diagnostician is operating. As Agnes Gagyi and Marek Mikuš and the contributors to their Special Feature on Swiss franc-denominated mortgages in Eastern Europe show in this issue, the politics of crisis can take many forms—some of which can become system-challenging, but most of which are system-conserving. Talking about and thinking the urban through the lens of crisis can be aligned with the intellectual tradition that Neil Brenner, writing in these pages, identified with ‘the search for emancipatory alternatives latent within the present, due to the contradictions of existing social relations’ (Brenner Citation2009, 201). Or it can be a form of what Marx and Engels scorned as ‘critical criticism’ (1956 [1845]), a passive moralism which seeks to identify problems without transforming the world. There is a certain irony in the fact that crisis is not necessarily a critical concept.

Crisis has long been urbanisation’s shadow, or its twin. Ancient understandings of the urban conceived of the city as an idealised model of order, but the modern sense of urbanisation has always been intertwined with the experience and perception of crisis. Raymond Williams argues that both the pastoral and the urban were envisioned in the wake of the destruction of agrarian life at the hands of early forms of industrialisation and financialisation, a process that spurred an inescapable social crisis as well as a ‘crisis of values … a deep and melancholy consciousness of change and loss’ (Williams 1973, 61). Since the 1950s there has been a specifically American understanding of a singular ‘urban crisis.’ Drawing on a long history of elitist, racialised anti-urbanism, this term originally referenced the conflicts and limitations of the Fordist-Keynesian city, before gradually shifting to a focus on the breakdown of the New Deal coalition and the emergence of neoliberal urbanism (Weaver 2017).

‘Crisis’ has its etymological roots in the historical practice of medicine and referenced a point where a decision must be made. To many observers, something about capitalist urbanisation has always seemed unwell. But as critical urban theorists have long known, crisis tendencies are baked into the system. ‘Crises are the real manifestation of the underlying contradictions within the capitalist process of accumulation’ (Harvey 1978, 111). In the capitalist city, crisis is a permanent, recurring condition with which urban ruling classes are always grappling in one way or another. But for urban disaster capitalists and others for whom a good crisis should never be allowed to go to waste, periodic manifestations of crisis are also an opportunity to destroy and profitably remake the cityscape (Madden 2021).

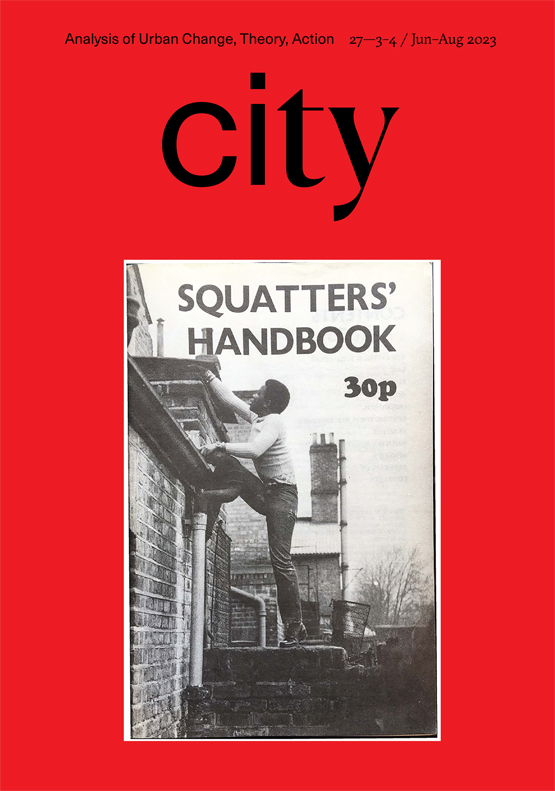

Today, talk of the crisis within global urban capitalism is ubiquitous. In one notable usage, a collection of downtown business interests, newspaper columnists and academic economists are promoting the idea that American cities face an ‘urban doom loop,’ where remote work, declining demand for office space, social service cuts, and middle-class flight threatens to initiate an unstoppable municipal spiral into fiscal and social chaos (Edsall Citation2022; Leland Citation2023). In Britain, invocations of the housing crisis are routine, raised by MPs including Jacob Rees-Mogg and Keir Starmer to reinforce their chosen strategies. More generally, the economic historian Adam Tooze has argued that the world has entered a state of ‘polycrisis’ (Whiting and Park 2023), popularising a term for complex problems with multiple intersecting causes and no simple solution. In use in various ways since the 1970s, polycrisis has been uttered by figures such as the complexity theorist Edgar Morin and the former European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker. Now it is regularly discussed by investment advisors, management consultants and World Economic Forum attendees. In 2023, even the staunchest establishmentarians evidently have no problem talking about crisis.

click here to read the full editorial.