City: Vol 24, No 5-6

City: Vol 24, No 5-6

founding editor: bob caterrall

editor: city editors

editorial: The urban process under covid capitalism

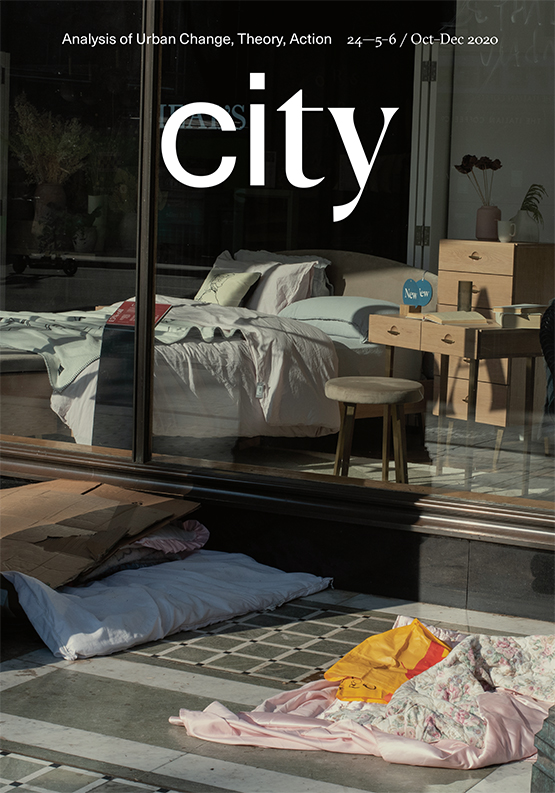

The covid-19 pandemic is a public health crisis, but it also fits into a broader pattern of capitalist crises and bears their tell-tale sign: a widening, painful divergence between that which is socially necessary and that which is economically viable. From housing and health care to social infrastructure and basic working conditions, the political-economic status quo has been revealed as incapable of meeting the needs of everyday life. Urbanisation is not coming to some kind of lugubrious end, as many commentators were arguing earlier in the year (see Madden 2020). Yet covid-19 has made it impossible to deny the fundamental brittleness of neoliberal urbanism. And it appears to have already inaugurated a new phase of urban political-economic recomposition, realignment, and restructuring.

Recent urban history has been punctuated and periodised by crisis. Following the global financial meltdown of 2007–2008, cities in Britain, America, and elsewhere turned, in various and variegated ways, towards a distinctive expression of neoliberal urbanisation (Beswick et al. 2016; Fujita 2011; Tonkiss 2013). Cities became sites of increasingly punitive austerity that was at once generalised as well as targeted at specific classes, social groups, racialised populations, housing tenures, and migration statuses. Aided by state policies and new technologies, speculative global investment was channelled into any available cranny in the hyper-commodified and financialised urban landscape—including housing at multiple scales and morphologies, from single-family suburban homes, tiny houses and trailer parks to central-city high-rise flats, co-living ventures, and district-sized megaprojects. Platformisation and other emerging forms of digital connectivity began to significantly reshape corporate strategies as well as techniques of urban governance (see Barns 2019). And the institutional drive towards transborder mobility began to confront a resurgent territorial nationalism that violently repudiated many elements of globalisation even as it took for granted other aspects of it. There has always been a repressive element of neoliberalism, but post-2008 its authoritarian dimension became increasingly prominent.

If those were some of the outlines of one dominant model of urbanisation that followed the last decade’s global financial crisis, what seems to be percolating in today’s emergency? It is far too early to determine the outcome of the multiple crises of 2020. But it is possible to observe some distinctive conflicts and pressure points emerging in urban life under what Tithi Bhattacharya and Gareth Dale call ‘covid capitalism’ (Bhattacharya and Dale 2020). None of these developments are unprecedented. But they are flashpoints that suggest some of the contours of the emerging paradigm of urbanisation after covid.

One of the major sources of conflict of covid-capitalist urbanisation is the prioritisation of rentiers over workers. When the pandemic struck, the state at multiple levels acted swiftly to protect the interests of property owners. Policies regarding housing finance and property tax were swiftly altered to try to maintain real estate values. But rent relief was left up to the discretion of landlords. Many cities and countries instituted temporary eviction moratoriums and other protections for tenants, but these programmes have been time-limited and insufficient. Meanwhile, work was transformed by lockdown and social-distancing measures in highly uneven ways. Unemployment has hit its highest levels in decades. Some professional and managerial work could continue in sheltered, Zoomified form. But essential workers—many in poorly remunerated but socially vital roles—were required to continue showing up. Other types of work have been put on hold entirely. The overall situation is both unjust and untenable: work has become inconsistent and uncertain yet the rent continues to steadily accrue. This is the direct result of unfair bailout policies, but it is symptomatic of an underlying power dynamic. Under covid capitalism, pre-existing tendencies towards rentierism are accelerating.

Another distinguishing feature of today’s urbanisation is the rise of crisis opportunism. Investment firms are looking to gorge on distressed assets and real estate debt. Delivery companies, fulfilment centres and retailers see economic turmoil as a chance to hire desperate workers on insecure contracts. And some companies are seeking to profit directly off social misery, such as the start-up pursuing a business model that has been described as ‘Uber, but for evicting people’ (Rodrigues 2020). In a period marked by the overproduction of social suffering, some firms see this suffering as a bounteous resource to be exploited. Disaster capitalism is being normalised, rescaled, and extended into new corners of urban life.

It is also clear that covid is becoming a new ideological keyword. Just as the ‘war on drugs’ and ‘war on terror’ became pervasive justifications for reshaping urban spaces in myriad ways, the pandemic response—sometimes explicitly styled as the ‘war on covid’—is already proving to be a powerful legitimising principle for a range of political projects. As with these earlier urban ‘wars’, the meaning of the pandemic and related ideas about ‘covid safety’ and the economics of recovery are floating signifiers. In Britain, the political and ethical urgency of responding to the pandemic is being put to a range of uses. A major, market-oriented revision of urban planning rules that has been in the works for a long time is now legitimised by the need to (in Boris Johnson’s words) ‘build, build, build’ the UK out of the pandemic. Covid is also used as a pretext for expanding the role of tech firms and algorithms in urban governance. Alternatively, some social movements and municipal administrations have used the pandemic to justify progressive environmental or housing measures, pushed through on an emergency basis. So the ideological uses of covid are not unidirectional. But the hope expressed by some earlier in the pandemic that neoliberal ideology would be among the virus’s casualties (eg Mason 2020) has not been borne out.

to read this editorial in full, please click here.