CITY Interview: Debbie Humphry interviews Tom Slater in response to his delivery of the 13th David M Smith Annual Lecture at Queen Mary, University of London.

Debbie: You gave the 13th Annual David M. Smith lecture at Queen Mary’s University this year entitled ‘From territorial stigma to territorial justice: a critique of vested interest urbanism’. What was the most important lesson you learned from David M Smith?

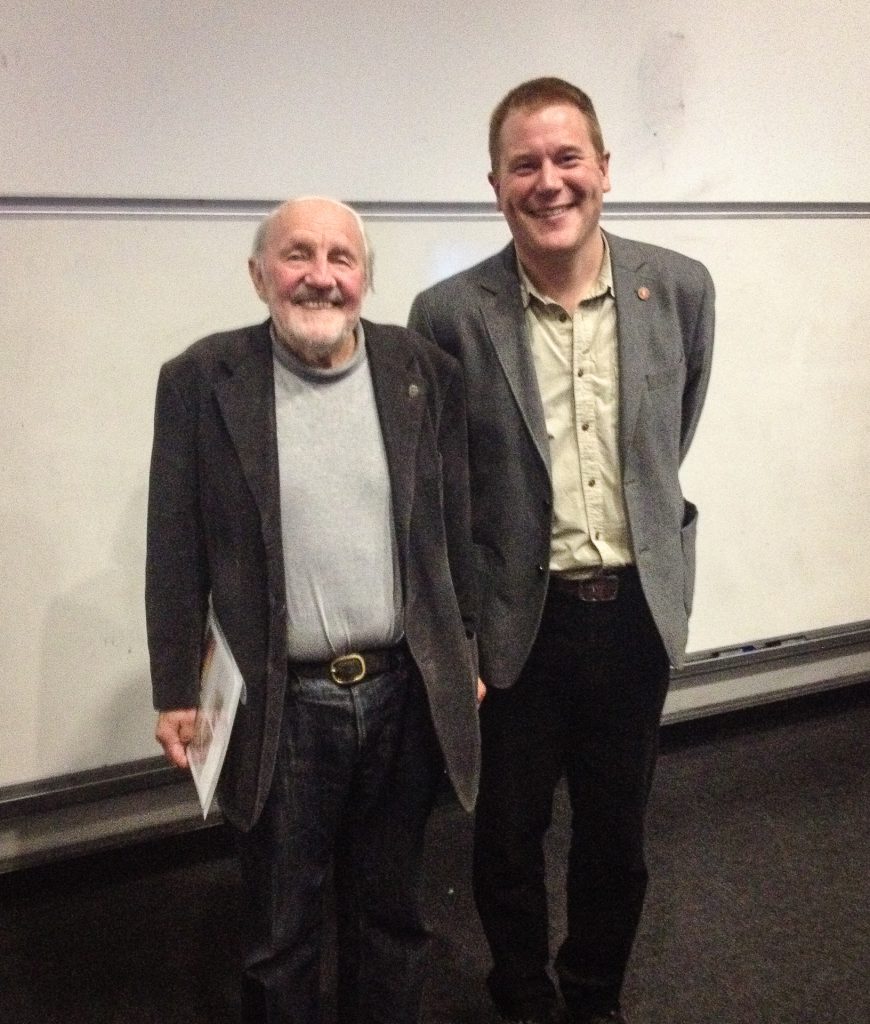

Tom: As an undergraduate (1995-1998), I took David’s course entitled Geography and Social Justice, and read the superb book he wrote with that same title. The whole experience was like being mentally electrocuted! It’s a very busy book, and it was a very busy course, one that covered many different theories of justice and the importance of thinking geographically when considering all of them – all brought to life by fascinating case studies. I soon realised that this was as much an education in moral and political philosophy as it was in human geography. David was inspired throughout his career by the 1954 words of August Losch, one of the great economists of locations and regions, who famously said, “The real duty…is not to explain our sorry reality, but to improve it.” That duty to improve our sorry reality ran through everything David did, and he conveyed it with gripping passion and enormous integrity. It was an honour to give the lecture and to see him there in the front row with his daughter.

The most important lesson from David, for me? That social justice should never be left to market forces. Instead, David argued that, given the chance of birth (that is, the chance of to whom you are born and particularly where you are born), and given the grotesque inequalities between people and places, social justice should be a process of equalization. He argued that this should be a process that places constraints on the inheritance of advantages such as wealth, land and political power; and in terms of other spheres like education, health care and the law, a principle of strict equality according to human need should apply, so as to give people the same capabilities in society. Informed by decades of mixed-methods research in very different places, David’s argument was: the more equal a society, the better for everyone in that society. He was making this argument way, way before anyone was talking about a book called The Spirit Level. Crucially, his work was a critique of uneven geographical development, anchored in a universal commitment to the equal realization of what is minimally required to be, and to feel, human. As all human beings have no choice but to occupy a place in the world, and as place is so central to human existence in so many ways, David argued that not being involuntarily banished from a place is a very solid principle and a building block for social justice, anywhere. These are lessons I hold close to me whenever I think about poverty and inequality.

You applied the theory of agnotology to research on UK right-wing free-market think tanks. Could you summarise your argument?

One of my favourite writers, the late great James Baldwin, once said, “It is certain…that ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have.” A few years ago I started thinking seriously about the deliberate production of ignorance when I was researching the political assault on the UK welfare state, and particularly the role of Iain Duncan-Smith’s think tank, the Centre for Social Justice (a splendid example of Orwellian doublespeak). Due to all the disinformation flying around about the welfare state and particularly the way in which numerous ridiculous unsubstantiated assertions from that think tank had informed devastatingly draconian cuts to benefits, I discovered that a conventional approach rooted in epistemology (the production of knowledge) became stranded. It seemed necessary to shift questions away from what people know about social issues towards questions about what people do not know, and why not. So I asked myself: what can we learn if the focus is shifted to the intentional production of ignorance?

Agnotology, coined by Robert Proctor, a science historian, is the word for the intentional production of ignorance. Proctor’s focus was on the tobacco industry’s efforts to manufacture ignorance about the health hazards of smoking. There are powerful institutions that want people not to know and not to think about certain things, and agnotology is an approach that traces how and why this happens. Given the world-historical catastrophes that took place 2016, it seems really important to understand how ignorance is produced; by whom, for whom, and (especially) against whom. Consider the fact that millions of Americans genuinely believe that a billionaire property tycoon is somehow an “anti-establishment outsider” who is going to “make America great again”. Consider the fact that millions of people in Britain genuinely believe that leaving the European Union will help fund the NHS. Consider the fact that the Tories in Britain are telling the electorate that there isn’t a “magic money tree” to fund public services, when it is estimated by the Tax Justice Network that £120 billion is lost annually through tax avoidance, fraud and collection errors. So, it seems to be the right time for studying intentionally-produced ignorance, and how it circulates.

I received unexpected feedback from people outside academia – particularly anti-poverty activists, opposition politicians and, astonishingly, senior police officers – that my critique of the Centre for Social Justice was useful to them, as not enough people have been going after these think tanks and what they have been up to. These institutions have become massively influential in the formation of policies on welfare and housing that have led to evictions and displacement on a disturbing scale. The housing crisis has become too important to ignore, and my argument in the David Smith lecture was that what we are seeing is a vested interest urbanism. Those who fund the think tanks and give them a voice are right at the heart of ensuring that there are certain things that people hear and read about and ultimately believe in respect of housing and urban issues, at the expense of some much more important things that people really should know about if we are to do something about the appalling inequality, poverty and social suffering we see in the UK. Quite simply, the vested interests that gain from housing and urban inequality don’t want us to know certain things! Crucially, the activation and amplification of the stigma attached to certain places is a key tactic of think tanks in order to control the narrative, and then what we see is territorial stigma becoming an instrument of governance. So for the David Smith lecture I tried to provide a thorough analytic dissection of the stigmatising tactics of the free market think tank, with a view to opening up political alternatives inspired by David Smith’s work.

It seems to me that one key element your argument about agnotology and post-truth have in common is the relationship between the production of ignorance and false facts for the purpose of influencing public opinion in order to perpetuate the interests of power. Clearly the deliberate production of false facts and ignorance for political purposes is age-old. But do you think we are in a particular historical moment where this is intensified? And if so why?

Certainly this is intensified and in terms of free market think tanks I think this has a lot to do with their shifting make-up and tactics. The early free market think tanks like the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA), the Adam Smith Institute (ASI) and the Centre for Policy Studies – the trio behind the Thatcher revolution of the 1980s – saw themselves as pioneers, as “the motorcycles ahead of the presidential car” (as an ASI employee once told Jamie Peck). They were certainly on a moral and political crusade, but they came into existence because of a deep hatred of state interference in the lives of individuals, borne of an ignorant fear of Cold War socialism. In their early think tank days, the economists working in them, as dangerous as they later proved to be, probably could make legitimate claims of being independent from politicians. They worked hard to get their unorthodox arguments into political circles, and they found the perfect recipient in Thatcher, who, true to form, was intent on creating a ‘market for ideas’. The IEA, for instance, would not exist had Antony Fisher, a wealthy battery chicken farmer, not formed a friendship with the economist Friedrich von Hayek, who of course was Thatcher’s economic icon and mentor. A very favourable constellation of circumstances led to quite marginal economic views becoming mainstream.

What has happened in recent years, however, is that the newer and most influential UK think tanks have actually become the presidential car. They are deeply political creations, started up and initially financed by wealthy politicians to advance their own agendas and to change the terms of the debate. What is striking to me, having trawled through their reports, is the astonishing, almost shameless intensity of their propaganda. The venomous zeal, the unwavering conviction, the simmering hatred of any view that doesn’t conclude that the ‘free market’ should be left alone and we’ll all be richer for it. As Jamie Peck has pointed out, these think tanks portray themselves as “lonely voices of reason”, as people somehow on the losing side, even though they shape and sail with the prevailing political wind. They indulge repeatedly in what I have called “decision-based evidence making”, yet they make repeated claims of objectivity, lack of bias and especially ‘rigour’.

Policy Exchange is a fascinating example. It was established in 2002 by three Tory MPs who had backed Michael Portillo’s campaign in the 2001 Conservative Party leadership contest. In his pre-trainspotting days, Portillo had advocated a modernizing shift towards more liberal social attitudes, whilst maintaining a commitment to Thatcherite economics. The day after Portillo withdrew from the leadership race, Archie Norman, former Conservative MP for Tunbridge Wells and the former CEO of Asda who masterminded its sale to WalMart in 1999, said that he was planning to finance a new think tank: “This is the future of the Conservative party and we would like to find a way of channeling that and harnessing it.” Nick Boles, currently Conservative MP for Grantham, was also involved from the start. Previously he had a modest business career supplying painting and decorating tools to the DIY industry, a career where he felt hampered by nuisances such as paying taxes. He describes Policy Exchange as his “biggest achievement in politics so far”. Francis Maude, now Lord Maude of Horsham, a fixture on Conservative benches for over 25 years, was the third founder. Maude felt that a new think tank should be free of the “Thatcher baggage” that he felt was affecting the older free market think tanks.

Policy Exchange was registered with the Charity Commission in 2003. Registering as a charity can provide numerous advantages for a think tank, as charities don’t normally have to pay corporation tax or capital gains tax, and donations to charities are tax free. But think tanks can also use charitable status to refuse requests for transparency in terms of who funds them. To be clear, many think tanks are charities, and many do in fact release information on who funds them. But my research indicates that the more right wing a think tank is, the less transparent it is. In 2007 Policy Exchange was investigated by the Charity Commission after a complaint was made that it was effectively a research branch of the Conservative Party. The investigation, incredibly, found no evidence of party political bias!

The theory of agnotology has a powerful resonance right now, at a time when the ‘fake news’ is being widely used, and discussed in the media, in what is being termed a period of post-truth. Could you comment on how the un-evidenced assertions and ideologies being produced by the free market think tanks you are researching either relate to, or are distinct from, the production of false facts we saw during the BREXIT campaign (such as the false promise of £350 million EU membership fees per week going directly the NHS), and that we regularly witness with Donald Trump?

They are very similar in many ways, but perhaps the key difference is the think tanks are more dangerous, as many of their false facts (lies) and absurd claims work their way into legislation and policy agendas as “evidence” without any debate. When think tank officials are quoted or interviewed in mainstream media coverage, their political orientation is almost never mentioned. What we are seeing is a new political economy of ‘expertise’ – it is unusual these days for academic publications and research findings to receive the same amount of media attention as think tank reports. Academic work that does not challenge the status quo tends to be the sort of stuff that gets significant media attention. Much of this has been fuelled by a systematic dismissal of academic research by neoliberal politicians, as the vast majority of social science scholarship and evidence is totally at odds with their rhetoric – but I also believe that the neoliberalisation of higher education in the UK has fuelled the subordination of scholarly to policy agendas. Countless academics have abandoned intellectual autonomy and framed their work in the dubious terms and categories of public policies in order to stand out in the push to secure external funding. The ‘impact agenda’, as I feared when it was first announced, has morphed narrowly into impact on policies way above impact on activists, grassroots struggles, the lives of people with least resources, and so on.

To return to the topic of your lecture: you talk about how most of the UK media overwhelmingly reproduces the market view on housing – such as the assumption that rising house prices are positive for the national economy, that home-ownership is an appropriate aspiration good, and that social housing estates are best demolished as they are nothing more than a trap for poverty and dysfunction. Why is this a dominant media position?

I don’t see this as just a media position – it is also a political position, a think tank position, and a position of neoclassical economists who have never been trained to see the world in any other way (or maybe do not want to!). In terms of housing, we have witnessed the reframing of a serious crisis of housing affordability as a crisis of housing supply caused by too much state interference in the market, or to use the terms of the neoclassical economists, ‘artificial manipulation’. Viewed through an analytic lens of agnotology, we can see a complete inversion going on: the structural and political causes of the housing crisis – that is, severe deregulation, rampant privatization, and attacks on welfare state – are put forward as desirable and necessary remedies that will make us all richer and squash an intrusive state apparatus.

The irony is that without the enthusiastic embrace of neoclassical logic by the neoliberal state, we would not be in this housing crisis. Neoliberalism couldn’t make inroads without the state. In opposition to the usual rhetoric that neoliberalism demands state retreat, in fact it actually requires continuous statecraft, and in ways that beggar belief. Take the infamous Right to Buy scheme. Over the past 37 years, over 3 million publicly owned homes have been sold off under that scheme. There are many declamatory debates on Right to Buy, but they tend to silence a pretty stunning contradiction, in that Right to Buy actually failed as a privatization strategy. 42% of all those who exercised their Right to Buy then sold on to private landlords, who then rented them to tenants at double or triple the levels of council rent, which required tenants to apply for housing benefit from the state in order to pay rent. So Thatcher’s flagship policy actually ended up costing the taxpayer far, far more in housing subsidies than it ever did in the provision and maintenance of council homes. How is that a successful privatization scheme, by any measure? It got the state knee-deep in housing expenditure! The main long-term effect of Right to Buy was to rob subsequent generations of affordable housing, diverting them into the landlord bonanza that is the private-rented sector – and now the state has to pay a vast sum of money (over 35 billion pounds annually) directly to landlords so tenants don’t become homeless. This is a truly preposterous situation, and it is tenants who have been suffering, most recently with the assault on housing benefit under austerity. The most outrageous thing of all? Many politicians have been profiting from the vast expansion of the private rented sector – one in three MPs are private sector landlords

I think in the UK one of the problems is the dominance of the neoliberal discourse across political, economic and media spheres is related to the turn of the left to the centre in the 1990s that we saw with New Labour, meaning that as a populace we have been bulldozed by a neoliberal ideology since Thatcher came to power in 1979, i.e. for 38 years – around two generations. Following the financial crisis of 2008 many on the left thought the public would recognize and reject the excesses of neoliberal capitalism when they witnessed bankers’ greed and their bailout by the state. Instead the opposite seemed to happen – and as you said in your lecture, the financial crisis was repackaged as a crisis of the welfare state –to be solved by austerity measures rather than control of capital. How did this discursive repackaging occur and why was it swallowed by the public? Has it been swallowed by the public? The last election perhaps indicates that the tide is turning.

I would argue that New Labour was a turn to the right from the centre! Since the late 1970s Britain has been subjected to an extraordinary neoliberal revolution. What began as a radical series of policy shifts towards privatization (a systematic assault on the Keynesian welfare state and on labour unions) has mutated into what Adam Tickell and Jamie Peck helpfully call “the mobilization of state power in the contradictory extension and reproduction of market (-like) rule”. This has fundamentally reshaped social relations from above, and led many to swallow and defend – passionately – the myth that economic growth is all that matters to a society as wealth will ‘trickle-down’ and benefit everyone. But housing wealth does not trickle down; it flows upwards, into the hands of lenders, investors, speculators, developers and housebuilding corporations. New Labour’s abysmal record on housing inequality paved the way for the 2010-2015 Coalition government, where the housing crisis deepened and intensified under the dominant Conservative Party (which campaigned using the language of compassion and social progress to shield the electorate from its rabidly right wing, ruling class and corporate ethos); and the subordinate Liberal Democrats (a small set of centre-right political lightweights without a coherent message or set of policies). David Cameron and George Osborne (both members of the British aristocracy with substantial family fortunes, who surrounded themselves with many more such people) were confronted by a substantial budget deficit which they argued was a consequence of reckless and irresponsible public spending by the previous Labour government. They even attributed the entire global financial crisis to the actions of that Labour government too, at any opportunity. The budget deficit was effectively a banker’s overdraft (big bail-outs of disgraced financial institutions) but you wouldn’t know it. For Cameron and Osborne, two archdeacons of low taxation and low public spending, there was only one way to deal with this budget deficit: a vicious austerity package, which, conveniently, was also an opportunity to destroy the welfare state that ‘Thatcher’s children’ of the Conservative Party so despise, and replace it with their dream of a thoroughly privatized and individualized society which would protect the sanctity of private property rights and a free market.

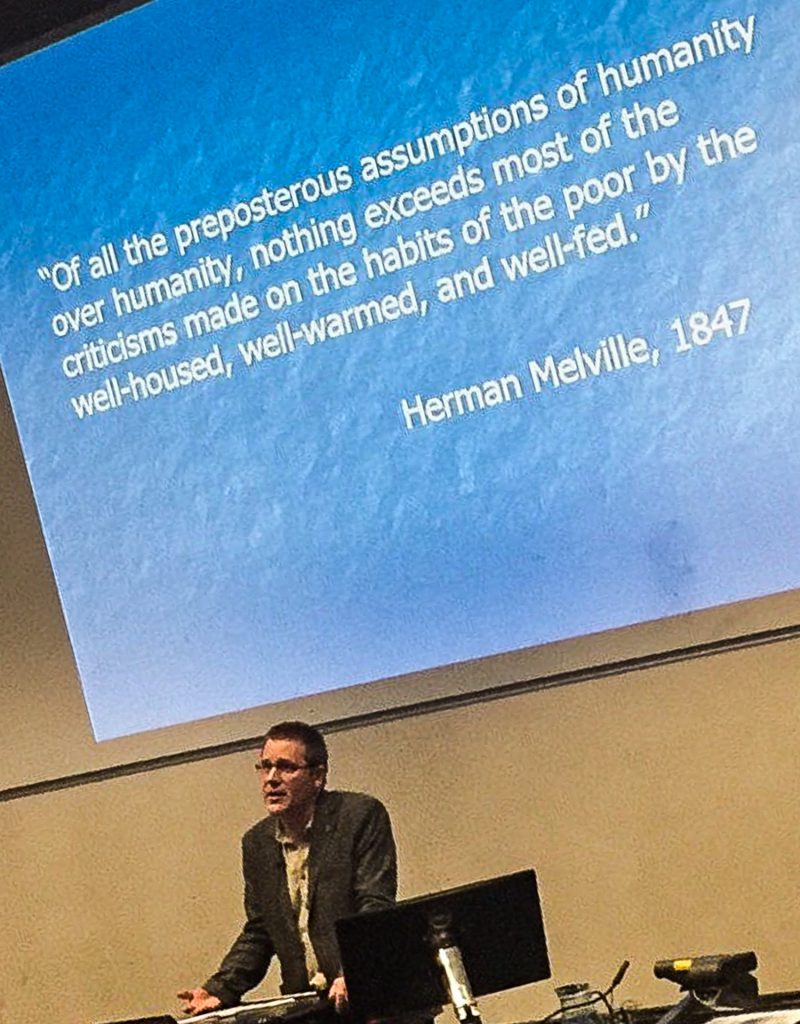

Symbols of the Fordist-Keynesian era such as the welfare state are viewed by Conservatives as dangerous impediments to the advancement of financialisation and the accumulation of wealth. British ruling elites have set out to monitor and monetize more and more of those human needs that were not commodified in previous rounds of financialization. Pensions, healthcare, education, and especially housing have been aggressively appropriated, colonized and financialised. For Conservatives, the redistributive path – increasing taxation of corporations, land and property – is not a matter for public discussion, and an entire cadre of cultural-technical ‘experts’ (chief among them think tank economists) is in place to make sure the conversation does not head in that direction. This ensures that it is largely unknown that just the money lost through tax avoidance alone could pay for 25,000 nurses on a £24,000 a year salary for 20 years; could put 130,000 children through school from ages 5-18; and would allow the government to give every single pensioner in the UK an extra £65 a year. There are so many simple statistics like that which could change the debate, but they never make the news. Another one: if food prices had risen at the same rate as house prices since 1979, a chicken would today cost £52! As you say, I think the tide is turning, but there is so much damage to deal with, and the not insignificant matter of the right wing mainstream media in the way of political consciousness.

Do you think the hold of the right wing market view of housing has taken hold of the public discourse and imagination to the extent of being hegemonic? – with the idea that the market is the solution to the housing crisis legitimated as the norm?

Without any doubt. Nearly 40 years of neoliberal housing policy, and the neoclassical economic logic undergirding it, has created an extraordinarily impenetrable belief system, with the core view that ‘high house prices mean good news for an economy’. When you have 99% of the press quoting the real estate industry, and think tank literature that says the market will always work for owners of property and for borrowers, no matter what, it is very hard indeed to get alternative views across. You would think that the 2008 financial crisis would have been a wake-up call in terms of what housing bubbles can do to societies, but it was revealing that the economists, politicians and financial sector all spoke quickly of returning to “normal” after the crash. The futile norm, for obedient debt-encumbered homeowners, is hoping that your property value will go up and everything will be fine in the end. ‘Resilience’ discourses, which have become so popular of late in academia and policy circles, are anaesthetizing in this respect: the logic seems to be, ‘bounce back from an economic catastrophe’, rather than ‘think about how that economic catastrophe happened’. I do not want to be resilient! I want to understand and challenge the systems and institutional arrangements forcing us to be resilient.

Savills’ estate agents are now key advisors for local and national government and in your lecture the Savills’ planning officer in the audience claimed Savills has over 200 local authorities as their clients for estate regeneration. I have attended talks and heard Savills present themselves as saviors of the housing crisis by – as they put it – releasing land value from council-owned housing estates into the private sector – enabling more properties to be built. But we know most of these houses will be for the wealthy, including the government-subsidized ‘affordable’ starter homes. Given that all the evidence indicates that housing estate regeneration results in a net loss of social housing and an increase in displacement of lower-income people, I would argue that Savills are producing a form of agnotology and ‘territorial screen’ (to use the terms of your lecture) that are hiding this reality . How can such a dominant discourse be challenged? How do we un-make the ignorance?

I agree with you here, and Savills is being either delusional or dishonest by saying it is the savior of the housing crisis. In April 2014 the Department for Communities and Local Government created a £140m Housing Estate Regeneration Fund, and then it commissioned Savills to investigate the potential of Policy Exchange proposals to demolish high rise social housing in London. In January 2016 the Savills report was published and was then used to justify a government strategy proposing to demolish 100 ‘sink estates’ in England. Although the Savills report did not make a specific call for demolition, it said, “We have assumed cleared sites.” But never mind the language – something strikes me as going dreadfully awry when Savills is commissioned as expert consultant on the matter of urban poverty on social housing estates, given that Savills’ expertise is in high-end, luxury and elite real estate markets!

Let’s think about this popular strategy of demolishing social housing estates and the logic undergirding it, which is that people who live on these estates tend to be poorer and more troublesome than people who do not. Let’s apply that same logic to health. People in hospital tend to be less healthy than people who aren’t in hospital. But I hope nobody would argue that to improve health, we should demolish hospitals! But land value is an interesting one. We can certainly ‘release land value’; just not in the way Savills wants to do it. Land value is never created from land ownership. It is created from collective social activities and investments on land, from the productivity of organisations and workers. But a monumental problem is that the Land Compensation Acts (1961 in England and Wales, and 1963 in Scotland) require landowners to be compensated for land as though it had planning permission, so any uplift in land value flows straight to landowners. So right now, landowners are pocketing a total of £9billion of profit per year from doing absolutely nothing. We are in a crazy situation: the rewards of rising land values in cities flow to the indolent! This encourages rampant speculation: the urban land market has become a place for very wealthy rentier capitalists – especially investors from overseas – to park their money at an annual rate of return of around 10%. Speculation means that more and more capital is being invested in search of rents and interest and asset pursuit and asset stripping, rather than invested in productive activity. Neoclassical economists get very flustered when you point this out, but it’s worth reminding them that even Adam Smith argued that England’s landowners were a major barrier to increasing the wealth of the nation. By grabbing and then bidding for land among each other, they were able to maintain high land prices and line their own pockets at everyone’s expense. John Stuart Mill, who was also rather partial to free market economics, became so frustrated with the behaviour of landowners he argued that they were not fit to play any role in maximising aggregate utility. £9 billion per year from rising land values – that’s a lot of money right there to house a lot of vulnerable people affordably and securely. But landowners now pocket all of it. So, both Land Compensation Acts should be repealed, and land value taxes are an urgent priority to prevent speculative landed developer interests from damaging cities and societies even more.

And is an attack on discourse enough? Discourse justifies policies and the substantive material production of inequalities, such as the austerity measures that are making people homeless and hungry, with Savills embedded in positions of power making financial deals with councils, homes being demolished and thousand of people being evicted and displaced. But how do we stop these material effects already so far down the line?

An attack on discourse is never enough, but by the same token, it is never enough to address the social disasters that surround us without a focus on symbolic power. The literary critic Kenneth Burke had a lovely phrase when he spoke of “terministic screens”. Certain terms are selections of reality that can quickly function as deflections of reality; as screens that hide what is actually going on if you were to take the trouble to look closely, or if you take the trouble to look at any ethnographic work going on places that are stigmatised. The “sink estate”, first used by The Daily Mail in 1972, and amplified significantly following Tony Blair’s visit to The Aylesbury Estate in 1997, is surely one such terministic screen. It makes it a lot easier to justify bulldozing a place to the ground and displacing its residents if that place gets repeatedly condemned as an incubator for the social ills of the world. We can also see terministic screens in the Housing and Planning Act passed in 2016, which allows social housing estates to be reclassified as ‘brownfield’ sites – a category normally reserved for contaminated ex-industrial land. The symbolic erasure of homes and entire communities paves the way for their literal erasure. We know from Bourdieusian scholarship that symbolic structures don’t just reflect social relations – they help constitute them. So material effects are fuelled by symbolic structures just as much as they are fuelled by economic and political structures.

We are seeing resistance on the streets, for example in the explosion of housing activist protests – Axe the Housing Act, Radial Housing Network, The Living Rent campaign in Scotland that you mentioned, FocusE15 and Generation Rent to mention a few. At the same time I hear many members of the public talking about the inevitability of regeneration and gentrification and social cleansing. How much hope is there that the powerful ideas produced by the free-market think tanks can be challenged in a way that meaningfully shift the public debate and neoliberal dominance?

These protests have achieved remarkable things against the odds, which gives me (and many others I know) a lot of hope. The huge difficulty is that the free market think tanks are bankrolled by very powerful interests, and speak the language of the dominant, whereas the housing activist organisations have hardly any resources at all and have a mountain to climb. Those who call the shots in the housing industry have a huge amount to lose, and they are willing to do whatever it takes to protect their privileges.

The vast majority of housing economists are trained to think in the neoclassical way: it’s all about striving for equilibrium in supply and demand. I have a wonderful cartoon in my office, which shows an economist saying to a homeless person, “The fundamentals of the economy are in great shape.” The homeless person responds, “But I am not earning enough to survive!” and the economist replies, “That’s not one of the fundamentals!” To a neoclassical economist, the housing crisis is a basic economic conundrum – too much demand and not enough supply – and the ‘solution’ is thus to increase supply by stopping all government interference in the competitive housing market, which (true to neoclassical beliefs) must be allowed to operate free of cumbersome restrictions to provide incentives for producers and consumers to optimize their behaviour and push the market towards equilibrium, whilst yielding the maximum amount of utility for the maximum number of people. I think housing activism, if it is to be effective, has to shatter the blatant lie that the housing crisis is created by too much demand and not enough supply. There are over 750,000 empty homes across the UK (and that’s before counting empty 2nd homes). If house prices were simply about supply and demand, then that massive surplus of homes would surely result in falling prices. But that’s not happening, so the crisis cannot be about supply and demand. Economists call for even more deregulation in the form of ‘planning liberalisation’ that would lead to the construction of new housing on greenbelt land currently shielded from housing development by government red tape. This is absurd – if we think of the deregulation that led to the housing crisis, they are like quack doctors applying leeches to themselves. The really important questions that need to be asked are: what kind of housing is to be built, by who, who for, and on whose land?

Rent control has to become a central battleground for housing justice, just as it has in Scotland. Just hearing the words ‘rent control’ is deeply unsettling to people who believe in so-called ‘free’ and competitive markets and in private property rights. The usual argument advanced by neoclassical economists is that if you had rent controls, landlords would all withdraw their properties from the market immediately, leading to a severe shortage of rental housing supply. This is simply not supported by the evidence where rent controls are well established, and also totally absurd: if landlords are told they can only charge £1000 rent for a property and not the £1200 they want to charge, they are not all suddenly going to go on strike and forgo the entire £1000! Also, imagine if housing benefit was under a different kind of attack, via modest rent controls. Reducing private rents by just one fifth would save £4billion annually in housing benefit – money that could then be used by councils to construct desperately needed housing. It was interesting that when Living Rent published an interview they did with me, where I dispelled some of the mythology around rent controls, two people at the Institute of Economic Affairs got hold of it and instead of engaging in a constructive debate, they felt it necessary to take to Twitter and attack the entire discipline of geography. It showed me that they have a lot to lose, and are scared of losing it. There is a world of difference between a home-owning economist working in a think tank being paid to argue against rent control, and a very low-income tenant struggling to pay scandalously high rents whilst feeding and clothing their children.

There seem to be different levels at which the production of false facts, un-evidenced assertions and ignorance occurs. In your talk, for example, you refer to the deliberate production of ignorance – implying that the think tank authors are self-consciously producing lies or at evading evidence in order to forward their views and interests. Yet you also refer to the “Impenetrable belief systems” of these authors, in which case their unswerving convictions are perhaps perceived by them to be sufficient unto themselves, and do not require evidence. In the first case there is a chance of undermining their view through some fact-finding – in the way that a house of cards may topple when you remove one. But in the latter case the facts are less likely to make an impact on their views, as they are made of a stronger, inflexible material. What would be your analysis of their position? Deliberate lies? Or convictions untouched by the truth?

The horrendous housing policies we have seen since 2010 have mostly come from the pen of someone called Alex Morton, who used to work at Policy Exchange until he became David Cameron’s special advisor on housing policy. One report he wrote in particular, entitled Making Housing Affordable (2010) quickly became Coalition housing policy (as did other things Morton wrote, notably a report called Ending Expensive Social Tenancies). The Making Housing Affordable report argues that social housing of any form is a terrible disaster on many levels, but particularly because it makes tenants unhappy, poor, unemployed, and welfare dependent. Not only is this baseline environmental determinism, it’s a reversal of causation: the reason people gain access to social housing is precisely because they are poor and in need. It wasn’t social housing that created poverty and need in the first place. The things he says about social housing in order to denigrate it come from cherry-picking various sound bites from a deeply problematic report on social housing written in 2007 by John Hills of the LSE, and also from numerous dodgy opinion polls that are treated as the definitive verdict on the topic. ‘Convictions untouched by the truth’ would be a very polite way of describing Alex Morton’s contributions to the debate on housing!

In the Making Housing Affordable report, having effectively argued that social housing is the scourge of British society, Morton proposes what he feels are solutions to the housing crisis. Predictably, they involve helping social tenants into home ownership and knocking down the ‘worst’ social housing estates and selling the land to developers. He ignores the land-banking epidemic facilitated by a system that actively rewards speculate-to-accumulate investment, and dismisses the importance of abundant mortgage credit and consistently low interest rates as factors behind the crisis (it’s not as if he doesn’t know about these things). He says the crisis is actually too much NIMBYism, so he proposes that fearful existing residents should be given “financial incentives” by developers to give their blessing to proposed new developments nearby. But what’s most disturbing about this report is setting the content against its title: making housing affordable. The whole report attacks the very idea of affordable housing, and suggests numerous methods to raise house prices and raise rents, with no shame at all. It’s people like Alex Morton who are behind the current madness of the 2016 Housing and Planning Act, which gives £20billion of taxpayer funds straight to big developers to build so-called “starter homes” (for which, in London, you need a household income of £77,000 and a deposit of £98,000). If that isn’t an upward redistribution of income from the masses to the tiny few at the top, then I don’t know what is.

Have you seen any shifts in the discourse or think tanks since May replaced Cameron?

No – they have just carried on hammering out the same predictable stuff, in the same “lonely voice of reason” way.

How can we make change? How can the left reclaim the discourse? How do we stop the neoliberal steamroller?

Redistributive and communal solutions tend to gain in popularity if the market is shown not to work in practice as well as shown not to work in theory, and I think there’s a lot more work to do there – and this work can only be done in collaboration with housing activists, neighbourhood organisations and tenant councils, who know far more than academics do about the misery of housing markets at ground level. Housing studies, as an academic field, can be incredibly boring and mainstream, and is still dominated by mindless number crunching and tedious cost-benefit policy analysis (as opposed to hard hitting policy critique rooted in a thorough understanding of political economy). Massive grants still flow to people doing this kind of work in “evidence centres” – almost always activist-free zones – and I see little positive change happening as a result of their work. I think a way forward would be for a global network of scholars and activists to form, comprised of people who know and understand that housing policy in several societies has quite simply become the financial ruin and displacement of the poor. Once we accept that, and I think we have to accept that based on urban uprising and struggles for housing justice, then some really exciting analytical and political work can be done.

Given that the right wing neoliberal discourse of fairness is premised on equal opportunities as a basis for the ‘fair’ competition for resources – a kind of survival of the fittest justification for inequality – how can an alternative discourse and policy approach of ‘justice is equalization’ be argued for and convince the public’? How can we ensure that the public understand the difference – as the right-wing use of the term ‘fairness’ can be quite beguiling?

‘Fairness to the taxpayer’ is a stupid way of considering what is socially just or not. I’m amazed by how ingrained it has become in recent years. As a taxpayer, if I consider something to be ‘fair’ to me, and you, also a taxpayer, do not consider that same thing to be fair to you – then what possible arbitration procedure could there be between us?! This approach gets us nowhere other than….if we paid no taxes, we would not have any disagreement! And this is precisely the direction in which certain right wing zealots want to take us. Far too many of us are under this spell.

A way out of this spell is to reclaim the language of social justice from the right. When pushed, people on the right can never define it. The Centre for Social Justice has never attempted to define ‘social justice’ – no definition appears on its website, nor in any of its publications. Only in a 2010 interview in the New Statesman did CSJ founder Iain Duncan-Smith attempt to define it:

“I mean to improve the quality of people’s lives, which gives people the opportunity to improve their lives. In other words, so people’s quality of life is improved.”

How’s that for vacuous tautology?! Most scholars of political and moral philosophy tend to concur that in the context of the distribution of any society’s benefits and burdens, redistribution in the context of inequality, or the defensibility of unequal relations between people, must lie at the core of any understanding of social justice. But ‘social justice’ has been hijacked by the right, to the extent that society is viewed by so many through behavioural filters such as ‘family breakdown’, worklessness, dependency, anti-social behaviour, personal irresponsibility, addiction, and out-of-wedlock teenage pregnancies – things deemed ‘unfair’ to the ‘hard working taxpayer’, and hey presto, social justice can be achieved if we make it harder for people in this situation by paying less tax! It seems to me to be crucial for any social movement to smash this hideous reasoning, to show that massive inequality hurts us all (we are all victims), and to reclaim social justice as a condition of striving for greater equality in all spheres of life (and that this is never something that can be achieved under neoliberal capitalism).

In your lecture you deploy a critique of right-wing free-market think tanks. Have you also looked at left-wing think tanks? And can they equally be found wanting in terms of the production of ignorance, lack of evidence and ‘decision-based evidence making’?

I have been looking at this, and I am starting to see that there aren’t actually very many left wing think tanks. Most identified as such are dull and centrist, or trying to shed the ‘Blairite’ tag with varying degrees of success! There are some left wing think tanks doing remarkable work, but they struggle for resources, and find it hard to make inroads given the prevailing political wind. The centrist ones usually operate firmly within the status quo and produce desperately boring documents working with the categories of neoliberal reason such as ‘resilience’, ‘community cohesion’ and ‘housing choice’. It’s all very depressing, and why I turn to activist organisations for actual insights!

You say there has always been territorial stigma attached to places of poverty, but that this has intensified in the past two decades – can you explain how? Are you talking about since the Coalition came to power in 2010? Or had a shift already occurred with New Labour?

It was happening under New Labour, but nothing like to the same degree as we have seen since 2010. It’s not a new development that certain parts of cities have negative reputations, but what we’ve seen in the last decade or so is that certain urban districts and housing estates have come to be widely renowned and reviled as epicentres of self-inflicted and self-perpetuating destitution and depravity. More than ever before, territorial stigma is activated and amplified to try and procure consent for punitive policies. The label “ghetto” is commonly hurled about to dramatize and denounce poverty, suggesting places ready to erupt in mayhem at any moment. There’s also profound gendering going on: we see the portrayal of entire areas as full of single mothers scrounging off the state, unable to control their numerous rampaging children, whilst the fathers are nowhere to be seen. When David Cameron gave a speech responding to the 2011 riots in urban England, he said this:

“I don’t doubt that many of the rioters out last week have no father at home. Perhaps they come from one of the neighbourhoods where it’s standard for children to have a mum and not a dad, where it’s normal for young men to grow up without a male role model, looking to the streets for their father figures, filled up with rage and anger.”

Another development is that when persons of power and eminence visit disreputable districts nowadays, it is not in the voyeuristic mode of the past but rather in a martial mode, to announce measures designated to root out rot, restore order, and punish miscreants.

Do you have any further comments in the light of what happened at Grenfell

This was a horrible, preventable and deeply political tragedy. There have been some excellent analyses already – all I would add to them at this juncture is that it is worth considering in depth whether political struggles could organize around the question of making it illegal for those with property interests to stand for public office. The Deputy Leader for the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, and the borough’s Cabinet minister for “housing and regeneration”, is a man called – I kid you not – Rock Hugo Basil Feilding-Mellen, son of the Countess of Wemyss and March. He has a lot of questions to answer about Grenfell and he appears to have gone into hiding!*

I clashed with Feilding-Mellen back in 2013 as his family owns all the land around Longniddry, the village east of Edinburgh where I live (as well as large swathes of southern Scotland and Gloucestershire), and he wants to build a lot of expensive houses here with his company “Socially Conscious Capital” (a pure exemplar of a contradiction in terms if ever there was one!). He ran roughshod over residents’ concerns and treated us all with arrogant dismissal and disdain – and our campaign against his plans for the “sustainable expansion of Longniddry” resulted in him reluctantly reducing the amount of houses he wants to build here (which of course are not going to be ‘affordable’ like he claims, and certainly not ‘sustainable’ as they involve ripping up excellent arable land and replacing it with concrete).

Anyway. It speaks volumes about the grotesque inequalities of wealth and power in British society, particularly acute in Kensington, that Feilding-Mellen is even in a position where concerns of poor residents in Kensington have to be addressed to him (and other Tories on the Council with property development interests). Not only have they ignored the concerns (multiple sources confirm this, and are well documented on the Grenfell Action Group blog) – they have done so whilst sprucing up the facades of ‘unsightly’ high rise social housing with dodgy cladding in a thinly-veiled intent to gentrify the area, which will cleanse the borough of the poor.

Nobody can control the circumstances into which they are born – neither Feilding-Mellen nor the tenants of Grenfell – so it beggars belief that we still live in a society where inheritance and land titles (and arbitrary electoral boundaries) can result in someone so removed from (and so indifferent to) the plight of working class people having the most say in their housing situation. Grenfell was a tragedy shot through with grotesque class inequality. If anything progressive is to come from the anger it has triggered, at the very least it should be that landowning, property developing, rent-seeking politicians should never be allowed anywhere near the question of providing safe and affordable shelter for people in the most housing need. This issue goes far beyond Grenfell – one of the global problems of our time is politicians with major real estate interests investing in developments that bring them profits, whilst disinvesting in the lives of people they are elected to serve. Grenfell is about far, far more than dodgy cladding, and certainly must never become an excuse for politicians ‘informed’ by think tanks to knock down high-rise social housing.

What are you working on now?

I’m trying to convert all my work on think tanks into a book entitled Vested Interest Urbanism – I just need more agreeable working conditions to write it! Hopefully that will be the case sometime soon, and when done, I hope it will contribute to numerous efforts to resist the appalling tactics of think tanks and their supporters, which have such serious consequences for so many people.

* Feilding-Mellen has since resigned as Deputy Leader of Kensington and Chelsea council, but he is still a ward councillor.

Recording of lecture: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D3a3-MlqF9M&feature=youtu.be

Dr. Tom Slater is reader of Urban Geography at the University of Edinburgh.

Dr. Debbie Humphry is editor and webste editor of CITY; Lecturer in Human Geography at Kingston University. http://www.debbiehumphry.com

CITY Website Editor: Debbie Humphry humphrydebbie@gmail.com

CITY Correspondence Editor: Anna Richter city.editorialoffice@gmail.com

CITY Facebook https://www.facebook.com/CityAnalysis/

CITY Twitter @CityAnalysis