Co-editors: Dr. Ulises Moreno Tabarez, Dr. Dulce María Quintero Romero, Dr. Héctor Becerril, and Dr. Rocío López Velasco

Editorial Note: This blog is part of an ongoing collective research effort under the project “coastal commons” (project code: USF-SSA-230311), funded by the urban studies foundation, supported by City, and managed by the centre for sustainable development management. It offers a personal testimony from an associate researcher, Chris del Valle, highlighting the damage and vulnerabilities experienced by communities on the geographic and social periphery of Acapulco. By sharing first-hand perspectives on the impacts of recent hurricanes, this piece seeks to shed light on the challenges faced by marginalised areas and contribute to a deeper understanding of urban resilience and its challenges in the face of recurring disasters.

A Reflection on Territorial Injustice in Times of Hurricanes

By Chris del Valle

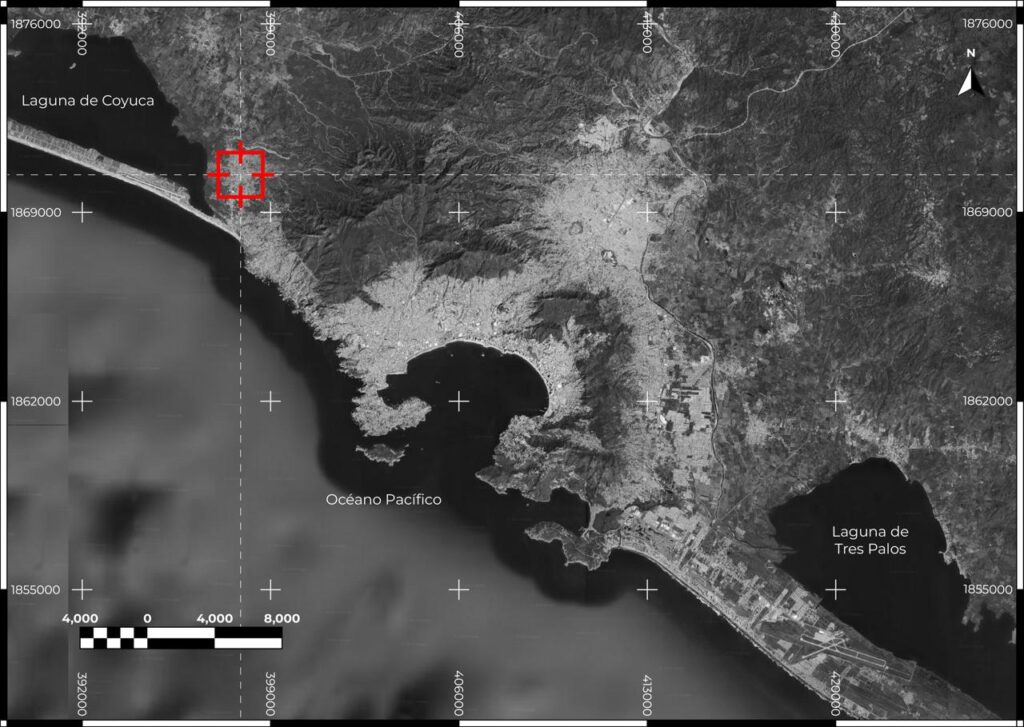

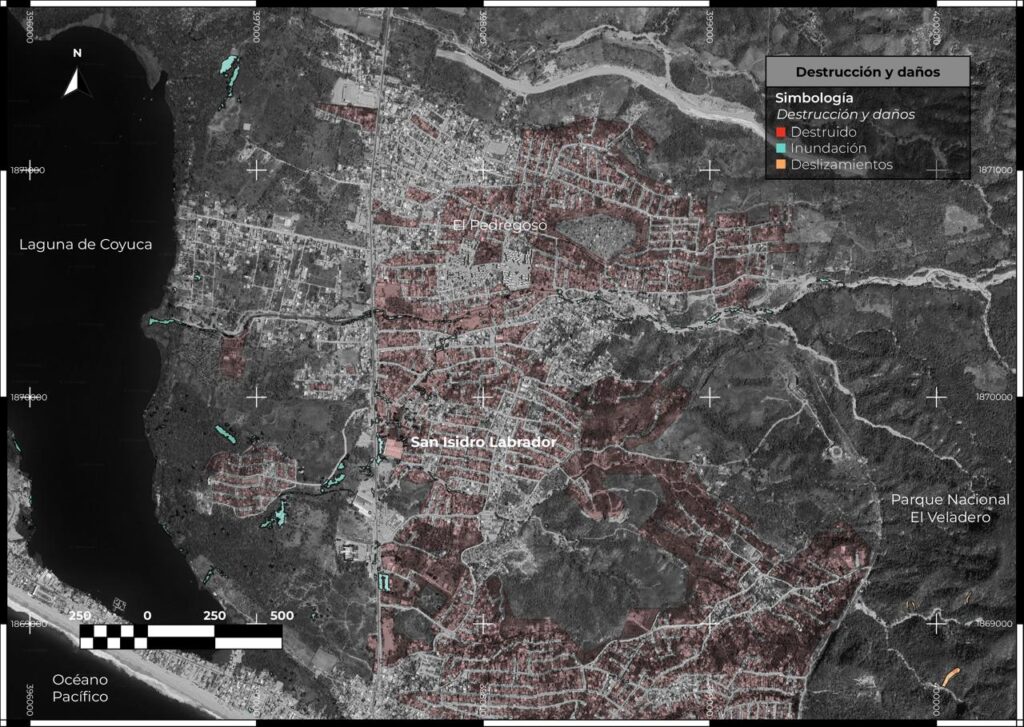

When classes are suspended due to heavy rain, families relax, make hot chocolate, and eat bread rolls. This could be the beginning of a love story, but this time, it turned into a tale of horror, as seen in the case of San Isidro Labrador (see Maps 1 and 2), a neighbourhood on the outskirts of Acapulco.

My personal experience with hurricanes has not been particularly dramatic, as I live in relative comfort, with my home not located in a high-risk area. However, in San Isidro, the situation was entirely different and deeply alarming.

I had the opportunity to research this neighbourhood (see Figure 1) as part of a series of ongoing studies at my institution, the acapulco institute of technology. I conducted a study on the damage caused by Hurricane Otis in 2023 and its impact on the residents, and the information I gathered was eye-opening.

San Isidro Labrador does not face the risks associated with steep slopes, as was the case during Paulina in 1997—the deadliest hurricane—which triggered landslides on the slopes of Palma Sola. At the time, survivors shared harrowing accounts on television of seeing dismembered bodies in funeral homes and corpses carried by the Camarón River, ending up on Avenida Costera Miguel Alemán. I learned about this from a 70-year-old woman I interviewed during my survey in San Isidro.

I have a hyperactive curiosity about how people react to certain circumstances and instinctual impulses in contemporary society, as well as a passion for history, which reveals why things are the way they are today. I found it particularly striking that the same root causes led to similar levels of devastation in Acapulco during the hurricanes of 1997 and 2023. These cascading effects ultimately impact neighbourhoods like San Isidro. This is not simply a consequence of hydrometeorological events but rather a manifestation of socio-territorial inequality. These natural phenomena only serve to highlight these injustices, which I will discuss further.

Although San Isidro is not at risk of landslides, it faces another significant threat: the arroyo (stream). This became starkly evident during Otis in 2023. The arroyo is undoubtedly the most troubling aspect of the neighbourhood, as people have settled along or near its banks. This was the primary cause of the widespread devastation in the area.

According to the testimonies gathered during my research, residents shared a common experience during and after Hurricane Otis: total confinement. The air was both humid from the rain and aggressive, felling large trees like mangoes and palms. Sheets of aluminium, which were supposed to be securely fastened or welded to roofs, were torn away and crumpled like paper. There was constant fear that homes might collapse, along with the anguish of those who lost their houses or loved ones. Some people were forced to work, unable to focus due to the risks they faced.

In the aftermath, mud and mould covered everything (see Photos 1, 2, and 3). The “need” to loot became evident—whether from the stress of not knowing if there would be food the next day, the drive to survive, or simply because some items were unattainable luxuries in normal circumstances. The darkness from power outages, the cold at night, and the fear of burglars breaking into homes left people sleepless, causing exhaustion and distress.

Everything that happened profoundly impacted the average Acapulco resident. Every time it rains, a sense of danger takes over any calm, or in extreme cases, post-traumatic stress appears. Even I feel it. Personally, I live with the constant fear that the next hurricanes will be worse. In an online conference I was invited to attend, just hours before Hurricane “John” reached Acapulco, I heard they are considering creating new categories. Are global high temperatures such a pressing issue? It shouldn’t be a concern if we were doing what we should, but economic profit is far more powerful than environmental health. This premise is at the root of the socio-territorial inequality I previously mentioned.

Whenever the impacts and damages caused by a disaster in Acapulco are discussed, the focus is always on Avenida Costera Miguel Alemán and the entire bay area, as it sustains the economy of the municipality, city, and region. However, “Acapulco is not just the Costera,” is a common protest among residents who are repeatedly affected. Similarly, the support provided to these affected communities by the government is minimal.

It’s logical to predict that the coastal zone will be one of the most affected in terms of material losses, as it is the first exposed to the impacts of hydrometeorological phenomena. Due to strong winds, rising tides, and sandy soil, this tourist strip represents only a small percentage of Acapulco’s entire territory. In comparison, the rest of the territory consists of urban residential areas, green spaces, and internal bodies of water.

Every effort made to reactivate the economy and commerce in Acapulco’s coastal zone after a disaster becomes increasingly expensive due to various factors, both locally and globally. These include resource scarcity, the exodus of displaced tourists, material losses, crime and organised crime in the shadows, the migration and extinction of aquatic species, increased pollution, peso inflation, lack of government action, global warming… In short, Everything is interconnected, and every factor has an impact (see Photos 4 and 5). EVERYTHING IS INTERCONNECTED. The question is: who does it impact? marginalised peoples. Because they are neglected. Every attempt to reactivate the economy and commerce on the Costera impoverishes the population when it should be the other way around.

Some neighbourhoods recover: those near the coastal zone, housing developments that are insured, large corporate businesses, and some public green spaces. However, the majority do not recover, including neighbourhoods with high crime rates and those on the periphery. It is very common for peripheral neighbourhoods to be the most dangerous.

What struck me as particularly notable about this neighbourhood is that when I mentioned San Isidro Labrador as a research topic to a professor at my institute, they asked me which neighbourhood I was referring to. They thought I might be talking about “San Isidro Gallinero,” which is another municipality in Acapulco. If someone who has worked in urban planning for years is unaware of an area that faces such high vulnerability, I wouldn’t know what to expect from the general residents of Acapulco. This indicates that more than a few people are not even aware of the location or existence of the neighbourhood “San Isidro Labrador,” which is, in itself, a factor that heightens the vulnerability of this community.

Storm “John,” which evolved into a hurricane, might not have been as violent as “Otis” last year. However, the downpour caused flooding that, ironically, left the whole of Acapulco without even a drop of drinkable water. The stream overflowed as expected, and civil protection authorities had to intervene to evacuate people at risk to a temporary shelter until the situation settled. But the saddest part of it all is that the spirits and hopes of the population gradually fade every time a disaster occurs. This will likely worsen in the coming years. And even though nearly a year has passed since Hurricane Otis, “John” has only proven that the lessons from previous hurricanes served no purpose for Acapulcan society as a whole.

Chris Del Valle is an Architecture student at the National Technological Institute of Mexico, Acapulco Campus, currently working on a thesis focused on Sustainable Development.