Editors: – Dr. Ulises Moreno Tabarez; –Dr. Dulce María Quintero Romero; –Dr. Héctor Becerril; –Dr. Rocío López Velasco

As part of City’s commitment to exploring diverse urban experiences, we continue our blog series coastal commons. This project examines the intersections of urbanisation, coastal ecologies, and socio-political struggles in the Global South. With a particular focus on the coastal regions of Guerrero, especially Acapulco, Coastal Commons highlights how urban processes shape and are shaped by histories of environmental extraction, racialised geographies, and community resilience.

More broadly, City seeks to understand transformations in urban analysis, theory, and action in cities across the Global South, highlighting local voices and methodologies in the creation of their own interventions to address urban challenges. These situated experiences not only shape their own forms of urbanity but also challenge universal paradigms, demanding that regional theory engage actively with global debates.

peri-urban Participation in the Fight Against Neglected Diseases

By Dr Alejandra Gabriela Bárcenas Irabíen

My initial interest in veterinary medicine arose from a deep commitment to the well-being of living beings. However, as my studies progressed, I began to realise that the health of animals, humans, and ecosystems is intricately interconnected. The transmission of diseases between species, particularly in regions where agricultural and urban landscapes converge, made me aware that addressing public health requires a broader ecological perspective. This realisation led me to expand my focus beyond veterinary medicine to include environmental and human health, culminating in my research on neglected diseases in Guerrero, Mexico.

This blog is part of a series in which I document my long-term research on urban health, disease transmission, and community participation in Guerrero. Through these instalments, I aim to engage both local and international audiences in discussions on the intersections between urban studies and public health. In particular, I argue that urban health must extend its focus beyond city centres to include their peripheries, which are intrinsically linked to the well-being of urban populations. Drawing on the framework of participatory action research (par), my approach emphasises community-led health interventions, particularly in vulnerable and marginalised areas. Scholars such as jason corburn (2009) have highlighted the necessity of integrating community knowledge into urban health studies to create sustainable and contextually relevant interventions.

My work seeks to expand and deepen these discussions by examining how peripheral urban spaces contribute to the broader urban health landscape. My work with agricultural and livestock producers in the state of Michoacán gave me firsthand insight into the daily struggles faced by families in both rural and urban areas. The challenges they encountered in their efforts to survive inspired me to pursue a master’s degree in agricultural sciences in Yucatán. Later, after experiencing the realities of different regions and their distinct challenges, I felt the need to return to my home state of Guerrero, Mexico, to undertake a doctorate in environmental sciences. My research focuses on public health, particularly on neglected, tropical, and vector-borne diseases such as American trypanosomiasis, commonly known as Chagas disease.

Reports on the presence of triatomine insects in Mexico date back to the 1920s (Hoffman, 1928), with documented cases of Chagas disease emerging in the 1930s (Mazzotti, 1940). In Guerrero, the first publication on cardiomyopathy caused by Trypanosoma cruzi, the parasite responsible for Chagas disease, appeared in the 1980s (Reyes et al., 1983). However, research on this issue in Guerrero remains scarce, with only a few studies conducted between 1990 and the present (Bárcenas-Irabíen & Sampedro-Rosas, 2017). Despite Chagas disease being endemic to both Mexico and Guerrero, little effort has been made to study, prevent, or control its spread.

In 2015, as part of my doctoral research, I embarked on a project to address this issue, particularly in vulnerable communities within Guerrero—communities affected by natural or human-induced factors that contribute to the proliferation of disease-carrying vectors. The aim of my projects has been to complement the preventive strategies employed by governmental and health institutions to disrupt the natural transmission of neglected diseases, including Chagas. I have done so by leveraging environmental education and fostering community participation to cultivate resilience and self-sufficiency among vulnerable populations. My approach involves transmitting knowledge through dynamic, interactive, and educational activities designed for all ages, ensuring accessibility even for those who cannot read or write.

My first engagement was with the rural community of Texca, located just 30 minutes from the tourist hub of Acapulco. In Texca, one-fifth of the population has either no formal education or only basic schooling. This project began after the presence of Chagas-transmitting triatomine insects was confirmed in the area (Rodríguez et al., 2009). Recognising the urgency of the situation, I designed and implemented an educational and socio-community programme to address the problem, which had long affected the population. My dedicated team—including my husband, Johan David Hernández Álvarez—worked closely with local authorities, including the municipal commissioner, Cuauhtémoc Morales Rico, and the heads of the local primary and secondary schools. Their enthusiasm and willingness to engage with the project were invaluable.

With their approval and with the aim of exchanging ideas and understanding the concerns of the people of Texca, we organised a series of meetings as well as a round of fun, game-based group-integration workshops for both adults and children/young people in the locality. During these sessions, we carried out group activities to foster interaction between the project team and the community in order to build trust. At the same time, we took the opportunity to assess the community’s existing knowledge about Chagas disease (hereafter ‘CD’), its vector of transmission, and the preventive measures they already practised.

These findings served as a starting point for designing a series of educational interventions aimed at complementing local preventive strategies to interrupt the natural transmission of CD. They were specifically tailored to the population’s characteristics and divided into three workshops covering: (1) Chagas disease, (2) the triatomine vector and its habits, and (3) prevention and control measures. Each workshop utilised a range of methods to convey information and carry out activities, including oral talks and presentations supported by slides, videos, cartoons, comic strips, and informative leaflets. These explained what CD is, its phases, the signs and symptoms that characterise it, how transmission occurs, and its worldwide and national distribution—both for the disease and for the triatomine vector. Participants also learned how to identify the ‘kissing bug’, recognise its life cycle and various stages, detect its breeding sites, and apply prevention and control measures in their homes and community.

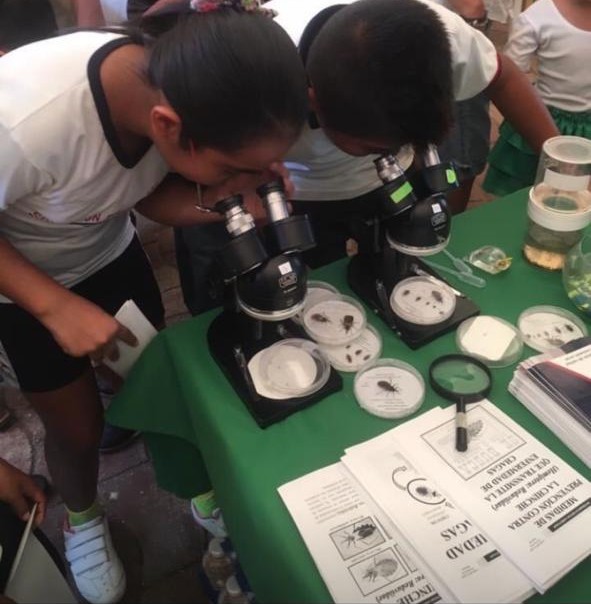

The workshops featured diverse activities. Children and young people coloured world and Mexican maps showing the distribution of CD, used foam figures to illustrate the disease’s transmission mechanisms and symptoms, and observed the vector’s life cycle through stereoscopic magnifying lenses. They also completed word searches, crosswords, and jigsaw puzzles, created costumes and enacted the life-cycle stages of the bug, played memory and lottery-type games adapted to the theme of CD, and made drawings and posters, among many other activities.

Alongside the workshops, and to complement the community’s epidemiological surveillance, participants were trained in the correct collection of triatomine specimens. This enabled residents to become permanent watchkeepers for their own community. We also conducted a series of entomological inspections in the homes of those who gave permission, searching for the bugs and transferring them to the Parasitology Biology Laboratory of the Faculty of Medicine at the National Autonomous University of Mexico for taxonomic identification and testing for the causal agent of CD, Trypanosoma cruzi.

It is important to note that, at no cost to the participants and thanks to the support of Dr Paz María Salazar Schettino and Dr Martha Irene Bucio Torres, infection by the parasite causing CD was identified among the children and young people of Texca (Bárcenas-Irabién et al., 2025). Those who tested positive received free follow-up analyses and were provided with appropriate treatment.

When the project concluded in 2018, all measured variables yielded favourable results. This success continues to motivate me to extend this methodology—previously documented in Bárcenas-Irabíen et al. (2017, 2014)—to other communities with similar vulnerabilities. From the very first contact with the community, observing the interest of its inhabitants and their active participation in the project, working alongside me as a facilitator, was profoundly rewarding. It reaffirmed my commitment to replicate this initiative in other at-risk localities.

My postdoctoral research is already underway. Future entries in this blog series will highlight the ongoing importance of this work, particularly in the aftermath of Hurricane Otis. The storm exacerbated existing vulnerabilities in the affected communities, making participatory health interventions even more critical in addressing both immediate and long-term public health challenges. Understanding urban health in post-disaster contexts requires integrating ecological and social dimensions, as environmental disruptions often accelerate the spread of neglected diseases. By expanding community-based strategies, we aim to contribute to more resilient public-health infrastructures that link urban centres to their peripheries.